Parallel Wave Function Collapse

Jan Orlowski and Amy Lee

Website: Parallel Wave Function Collapse

| Other Materials: Final Report PDF | Checkpoint PDF | Proposal PDF |

Summary

We accelerated a procedural image generation algorithm called Wave Function Collapse by introducing parallelism. To do so, we experimented with different CPU parallelization methods, such as using OpenMP or pthreads and different algorithms, comparing the results of each method to determine which was best. We found that we could get 2-4x speedup using openMP and also found a less-general sequential algorithm that outperformed all parallel implementations and did not parallelize well.

Background

Wave Function Collapse is an algorithm for generating large bitmap images that are locally similar to a small reference bitmap image. The bitmaps are NxN locally similar if each NxN pattern of pixels occurring in the output occurs at least once in the input, possibly rotated or flipped. Patterns may be tiled (see Fig. 1) or overlapping (see Fig. 2), and may have constraints specifying which types of tiles may be adjacent to other types of tiles.

Fig 1: Mapping between input patterns and tiled output pattern.

Fig 2: Mapping between an input pattern and local, overlapping occurrences in an output pattern.

Below is a high-level description of the (sequential) algorithm, adapted from the writeup at https://github.com/mxgmn/WaveFunctionCollapse:

- Read the input bitmap. Identify and count NxN patterns.

- For simplicity, we may format the input as a discrete set of NxN pattern patches.

- Create an array called

wavewith the dimensions of the output. Each element ofwaverepresents the state of an NxN region, or “cell”, in the output. The state of a cell encodes boolean coefficients that store information about which NxN patterns are forbidden (false) or not yet forbidden (true) for that cell. For each cell, we want to “collapse” the list of possible patterns until only 1 possibility is left. In the final output, the cell will be assigned that 1 pattern. - Initialize

wavein the pristine state, i.e. with all the boolean coefficients beingtruefor every cell. - Repeat until all cells have 1 possibility:

- Pick arbitrary cell(s) and randomly set one of its patterns to

true. - Reduce the possibilities of its neighboring cell depending on their compatibility with its pattern. These compatibilities are defined in the input.

- Pick arbitrary cell(s) and randomly set one of its patterns to

- By now all the cell must be either in a completely observed state (all the coefficients except one being zero) or in the contradictory state (all the coefficients being zero). In the first case return the output. In the second case we exit without returning anything.

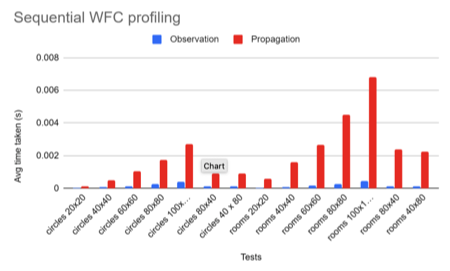

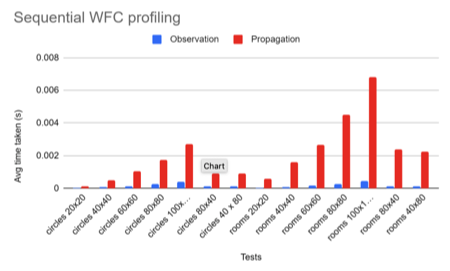

We profiled the original sequential code to identify which step was the most computationally intensive. The figure below shows the results of our investigation:

Seeing the results, we decided to focus our efforts on parallelizing just the propagation step.

In the C++ implementation, the model keeps track of the currently valid possibilities for tiles as a 3D array indexed by (x,y,t) where x and y are tile coordinates and t is the id of the possibility. Here is how the propagation algorithm is implemented in C++:

- Mark the observed tile as changed

- While there is any tile that is still marked as changed:

- For each tile in the grid:

- If the tile is marked as changed, check if any of its neighbors have their possibilities limited by the change in the tile. For each neighbor that does, eliminate those possibilities and mark the neighbor as changed. Unmark the current tile.

- For each tile in the grid:

The reason parallelizing this algorithm is tricky is for the following reasons:

- Reducing possibilities in a cell affects other cells, which creates a dependency. Luckily, a change that collapses possibilities can only collapse more possibilities (can’t increase the number of possibilities).

- The current propagation algorithm requires going over all the cells multiple times. There is no fast way of telling the number of times we need to iterate over all cells to have no remaining changes.

Approach

For simplicity, our project only dealt with the case where output patterns are tiled, rather than overlapping. However, the techniques we used could easily be extended to work for both. As starter code, we used a sequential C++ implementation of the WFC algorithm by Emil Ernerfeldt. For parallelization, we used OpenMP, C++ pthreads, and the boost library. Most of the work went into modifying the propagate function to parallelize it, but we also had to modify parts of the code for running convenience.

Multi-core Parallel with OpenMP

For this approach, we tried to parallelize the propagate function using OpenMP.

A key observation here is that, when tiles are propagating their states to the next iteration, they depend on the current states of their neighbors. However, each tile can check the states of its neighbors independently during each round of propagation, which is amenable to parallelization.

The propagation step can be broken down into several levels of iteration: the program iterates over every tile in the image; each tile iterates over its four neighboring tiles to check whether any of them changed state; each neighboring tile that changed state then iterates over the set of possible patterns to check whether any of them are still possible for the tile.

First, we parallelized the tile iteration. Initially, we enabled the assignment of one thread to each row of tiles in the image, and saw roughly 2-4x speedup compared to the sequential version. However, since each tile can check its neighbors independently, we decided to instead allow assignment of one thread to every tile in the image. Speedup was still roughly 2-4x, but was slightly faster than the row-wise assignment.

We also theorized that each tile would be responsible for roughly the same amount of work, as each tile has a fixed amount of neighbors (between two to four) and patterns to check, so we used a static assignment of threads. However, we found that using a dynamic (guided) assignment led to slight speedup compared to the static assignment, implying that work variation among tiles may actually accumulate after many rounds of propagation and lead to some work imbalance.

Finally, we considered nesting parallel loops to account for the iterations over neighbors and patterns. However, these led to poorer results than using a single parallel loop.

Multi-core Parallel using Lock-free queues and OpenMP

For this approach, we continued to parallelize the propagate function using OpenMP. However, we introduced further optimization by utilizing work queues.

A key observation is that, in our case, if a tile changes only its neighbors are affected. So, instead of looping over every single tile to check if any changes need to be propagated, we instead keep a queue of tiles that could change. Whenever we process a tile and find that a change occurred, we add its neighbors to the queue. We finish once the queue is empty (i.e. we finished propagating). This gives us a sequential algorithm, but also a new avenue for parallelization. Using a lock-free queue, we can have multiple threads grab tiles from the queue, process them and add new ones onto the queue if necessary until the queue is completely empty. Our hope would be that the contention from all threads accessing the queue would not slow down the execution too much and we will benefit from more threads processing tiles.

To set up the initial parallel algorithm, we used the boost library’s lock-free queue as the queue and also used an std::atomic_int to set up a special barrier. The barrier was added to solve a problem: when the queue is empty, it does not necessarily mean a thread’s work is done. It is possible that another thread could be processing a tile and will add the tile’s neighbors to the queue once finished. So, we should only finish when all threads see that the queue is empty. The barrier int is incremented when a thread is working and decremented once when a thread sees the queue is empty. If a thread checks on the queue and finds it is not empty, it increments the barrier again and keeps working.

Multi-core Parallel with pthreads

For this approach, we tried to parallelize the propagate function using pthreads. As opposed to OMP threads, where the assignment of threads to data is unknown to us, we theorized that we could explicitly assign pthreads to chunks of data in a manner that would take advantage of caching.

Our first approach was to statically interleave the pthreads and their assigned tiles. We then tuned the number of pthreads used to determine whether it influenced performance. However, this approach does not take advantage of caching, as interleaving the threads scatters the tiles that a thread works upon.

Our second approach was to statically assign the pthreads to blocks of tiles. We theorized that a blocked assignment would introduce some work imbalance, but could allow for better caching behavior compared to an interleaved assignment.

Other Approaches

Besides the approaches listed above, we also attempted to implement parallelization using ISPC tasks and CUDA. We were unable to produce working implementations due to incompatibilities in our machine configurations and base code, but believe that further research could yield promising results.

Results

As stated earlier, we focused our efforts on parallelizing the propagation step, which comprised most of the total runtime of the program. However, other steps with potential for parallelization include the observation step, which iterates over tiles to determine whether they are all in the marked state and the program should stop; and the imaging step, which converts the array of tile states to the colored pixels corresponding to the tile.

We ran each of our above implementations on a large set of sample inputs, where each input consisted of a set of image pattern tiles (ranging in size from 8x8 to 32x32 pixels) and a file specifying a set of constraints for the image tiles. To determine performance, we measured the total amount of time it took for the program to finish on a given input.

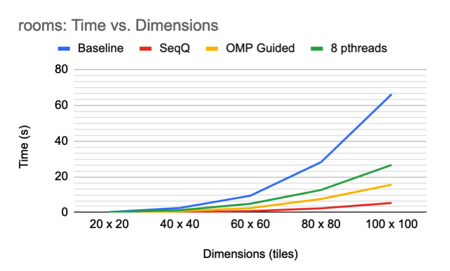

Below, we provide speedup results for a few selected sets of image tiles (called “circles” and “rooms”), with varying specifications for output dimensions (in terms of tiles) and tile constraints. We chose the “circles” set because it contains multiple tiles with no constraints. The “rooms” set also contains multiple tiles but many constraints. We show results for square outputs, but confirmed that rectangular outputs worked as well.

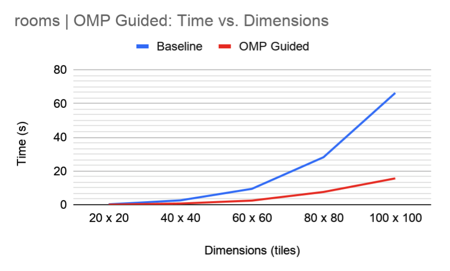

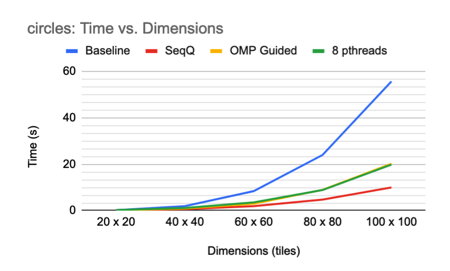

Multi-core Parallel with OpenMP

Results for this method are as follows:

As shown above, OMP parallel loops with guided thread assignment led to roughly 2x speedup for the “circles” set and 4x speedup for the “rooms” set compared to the baseline sequential version. Based on the graphs, it also seems that the duration of the program remains linear on the size of the output for both the baseline and parallel implementations. That is, we do not expect speedup to increase as the size of the output increases; However, we do expect the parallel implementation to be consistently 2-4x faster than the sequential version.

We theorize that the speedup is possibly limited by the maximum number of OMP threads that can be created and handled by each core at a given time. In addition, since OMP implementations rely on a master thread that distributes work among worker threads, there may be increasing overhead from distributing tasks that cancels out the time saved by having more threads.

It is also worth noting that the sequential implementation was faster for the “circles” set than the “rooms” set, but the parallel implementation was faster for the “rooms” set than the “circles” set. We stated earlier that the “circles” set has no constraints while the “rooms” set has many constraints. We theorize that the constraints may increase speed because they reduce the number of patterns that must be checked for validity during the propagation step.

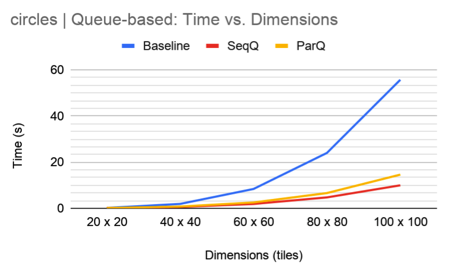

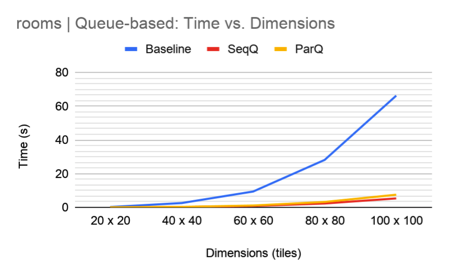

Multi-core Parallel using Lock-free queues and OpenMP

Results for this method are as follows:

In practice, the sequential queue algorithm completely outperforms the parallel queue algorithm. Contention is too large and leads to an overall slowdown in the parallel algorithm. We speculate contention shows up in the following ways:

- Threads often push to the queue, so there is time lost waiting to get access to push on the queue (even if it’s lock-less, threads can still push on the queue one at a time)

- The barrier is an atomic int shared across all threads. Incrementing and decrementing the int is bound to be costly.

As an experiment, we removed the barrier to see if we would reduce contention by a noticeable amount. This does mean that some threads may finish early, but in the case that all threads but 1 finish early, we’re just simulating the sequential case, which should give us a speedup. However, upon testing, we found that while there is a minimal speedup for most test cases (and a significant speedup for the test cases that performed especially badly in parallel), it was still nothing compared to the sequential queue algorithm speedup.

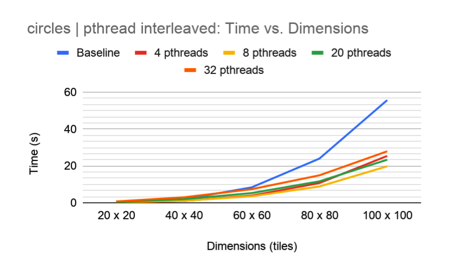

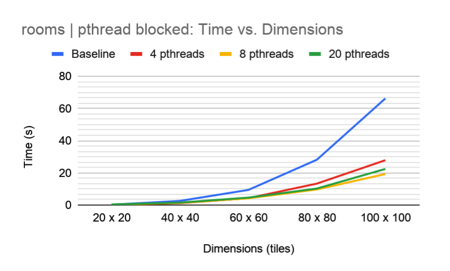

Multi-core Parallel with pthreads

Results for this method are as follows:

As shown above, the interleaved method outperformed the blocked method, with 8 pthreads being the optimal number of threads for each method. However, the pthread method consistently performed worse than the OMP and queue-based methods.

We believe that the interleaved method yielded better load-balancing than the blocked method; in fact, the blocked method failed to generate valid output when 32 pthreads were used. It also seems that there was little benefit to be had from caching, as each tile only accesses its neighbors once per round of propagation before their states are all updated. In addition, tiles accessing the same neighbor are always separated by that neighbor, which may interrupt spatial locality. And since the threads are working in parallel, the order of accesses is unknown and would make it improbable that a tile’s data would persist in the cache for long.

It is also worth noting that low pthread counts performed better on small outputs compared to high pthread counts: 4 pthreads typically outperformed all other pthread counts for outputs of dimensions 20x20 and 40x40. This may be due to the fact that high numbers of threads leads to very little work per thread when the output is small, and large overhead in creating the threads compared to actually using them for work. The program could benefit from a non-static number of threads: generate fewer threads for outputs of smaller dimensions, and more threads for outputs of larger dimensions.

Summary

A summary of the best results for each method is as follows:

Overall it seems that the sequential queue-based algorithm yields the best speedup compared to the baseline. Since it utilizes a work queue of updated tiles instead of examining every tile in the image, the fact that it outperforms the OMP and pthread implementations is reasonable. The OMP and pthread implementations examine tiles that have already been marked with a pattern and are thus performing unnecessary work on the order of O(N2) per round of propagation, whereas the sequential queue-based algorithm does not.

It also seems that pthreads perform worse than OMP, likely due to greater load imbalance: the pthreads are statically assigned, but the OMP threads are dynamically assigned, and neither method seems to draw significant benefit from locality or caching.

In the future, we would like to further research parallel implementations of the queue-based algorithm.

References

Gumin, Maxim. 2016, v1, “WaveFunctionCollapse.” https://github.com/mxgmn/WaveFunctionCollapse

Ernerfeldt, Emil. 2016, v1, “Wave Function Collapse in C++.” https://github.com/emilk/wfc

Merrell, Paul C. Model Synthesis. 2009. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, PhD dissertation. Accessed at http://graphics.stanford.edu/~pmerrell/thesis.pdf